Forest River’s Sunseeker Classic motor home is built on a Ford E-450 chassis, framed with vacuum-bonded laminate, and crammed with features the armchair outdoorsman would never consider. On the 31-foot model I piloted recently, those included a propane furnace to keep the cabin toasty in freezing temperatures, two refrigerators (one for the indoor kitchen and one for the outdoor one), three sleeping areas, and dozens of cabinets, drawers, and compartments to conceal disorder.

All that engineering was pretty satisfying at the campsite. On the road it was noisy, adding clatter and a little bit of mystery—honey, did you hear that?—to the task of keeping a 14,500-pound motor home upright going over winding mountain roads and through crowded interchanges. At least that’s how I saw it. Like a real RV dad, I was doing my best to ignore the complaints of the unhappy campers with whom I was sharing the cabin. My kids had been slugging each other periodically, and when the iPad ran out of juice they tossed markers in my direction. My wife, Eleanor, had a premonition somewhere in the Allegheny Mountains and was now certain our brakes were about to give out. And that was before I opened an artery in my hand with a hatchet and wound up riding an ambulance from an obscure state park to an emergency room, asking myself how, exactly, I’d come to believe this would be a relaxing vacation.

The Clark family in Elkhart.

Photographer: Lyndon French for Bloomberg Businessweek

It had started some months earlier, when I’d convinced the editors of Bloomberg Businessweek that we should visit Elkhart, Ind., where the world’s largest RV companies are based. Elkhart, which is about halfway between Ohio and Illinois and just south of the Michigan state line, may not be known as a tourist destination. But, as I’d insisted to Eleanor, it’s a surprisingly bucolic place, where Amish farms mix with factories.

The vaccine was just starting to become widely available when we arrived at the end of March, and RVs remained compelling to travelers understandably turned off by the idea of sharing an airport waiting room or hotel lounge with a nose-masking stranger. Meanwhile, large portions of the American workforce were continuing to log in to the office virtually, creating an opportunity for the younger and more adventurous to work from the road, integrating their jobs into the #vanlife. Even the Oscar-winning film Nomadland romanticized this lifestyle in its own way.

The pandemic has been good for owners of vacation rental properties and shareholders of Airbnb Inc. It’s also been great for the RV industry. After all, a motor home (or travel trailer, which is an RV you drag behind your car or truck) is like a halfway house to nature, perfect for indoorsy types who still enjoy national parks and retirees looking for a safe way to drive across the country to see their grandchildren. And so, starting last spring, people began canceling European honeymoons and going to RV dealerships instead. The motor-home-curious flocked to rental offices and Airbnb-style sharing websites. This drove so much demand for new RVs that by the time we got to Elkhart, help wanted signs were calling out from factory gates and roadside billboards.

Conventional wisdom says that workers and vacationers are on the road back to pre-pandemic norms. But it’s also possible that the sudden embrace of RVs signals the beginning of a longer-term trend—a future in which tech executives and second-grade teachers finish their last Zoom of the day, emerge from their respective travel trailers to gather around a campfire, and unwind over cold beers and hot s’mores. Let’s hope they’ll all be trained to chop kindling safely.

There was really only one way to find out how realistic that vision was. When the kids’ school headed into spring break, I took the family to Elkhart, picked up the Sunseeker, and hit the road.

The Sunseeker in action.

Photographer: Lyndon French for Bloomberg Businessweek

The vacation, such as it was, started at the Thor Motor Coach Class B plant in Bristol, Ind., right outside Elkhart. It was, to the extent such a thing is possible, ground zero for the RV boom—the place where the biggest company makes its hottest models. Although a cold front was threatening ominously, it was sunny. Inside, workers wearing T-shirts ducked in and out of a procession of Ram ProMasters that snaked around the factory floor. Plumbers, carpenters, and electricians did their thing. A horn would honk, and a van shell would roll down the line to the next station.

Indiana, where more than 80% of North America’s RVs are made, came to play an outsize role in the industry more or less by accident. In one version of the story, the son of a prominent Elkhart merchant was captivated by the travel trailers he’d encountered at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago and begged his parents for startup capital. His success inspired other entrepreneurs, and a network of companies sprung up to manufacture motor homes and supply the nascent industry with specialized suspension systems, gas ranges, and refrigerators. Over the decades, the ranks of once independent RV companies consolidated into a small group of conglomerates, the biggest of which are in Elkhart.

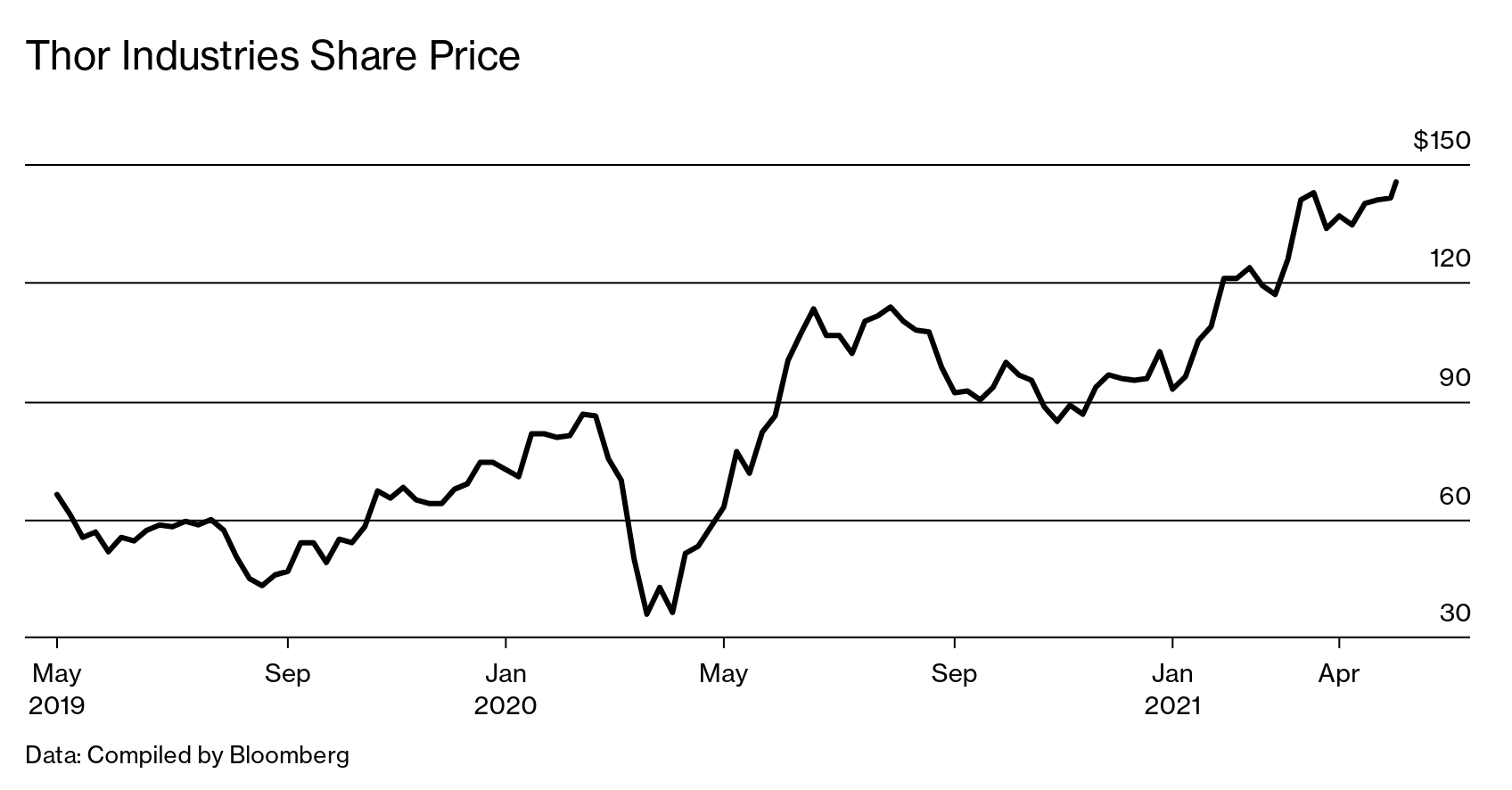

Thor Industries Inc., which accounted for roughly 40% of all RV sales last year, is one of them. The company was founded in 1980 by a descendant of the brewer Adolphus Busch and spent the ensuing four decades acquiring manufacturers, including Airstream Inc., Jayco Inc., and a dozen other makes you’ve probably gawked at on the highway. Thor’s lineage and its thirst for acquisitions make it a little like the Anheuser-Busch of motor homes. Forest River Inc., which is owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc., and which owns Coachmen RV, Shasta RV, and other manufacturers, is the second-biggest: the industry’s Heineken, as it were. Forest River is based in Elkhart, too.

Thor Industries Share Price

Data: Compiled by Bloomberg

Thor, like the rest of the industry, had been focused on building travel trailers and larger motorized coaches, which might have a washer-dryer and theater seating. But in recent years Class B motor homes—what the rest of us call camper vans—have been the fastest-growing segment. Class B vehicles are easier to drive without sacrificing too many amenities. Thor’s TMC Tellaro, for instance, is a 20-footer that can sleep up to four semicomfortably. Depending on the model, it can also cram in two propane burners, a microwave, a kitchen sink, a full (if tiny) bath, and an innovation called a cassette toilet—a commode that empties into a tank that works like a rollaway suitcase. That feature, I was told, is big in Europe.

Thor’s Martin.

Photographer: Lyndon French for Bloomberg Businessweek

Factories in Elkhart County shut down in March 2020 and reopened in May. But despite having been offline for two months, manufacturers delivered more RVs last year than they did the year before. More than 530,000 vehicles will be shipped to North American RV dealers this year, a record, according to estimates from the RV Industry Association.

“Our products were kind of built for something like this,” said Thor Chief Executive Officer Bob Martin, a former offensive lineman at Purdue University who spoke to me across the length of a conference table overlooking the scenic St. Joseph River. RVs had normally been the domain of snowbirds, motor sports enthusiasts, mountain climbers, pet owners, pro golfers, touring rock bands, and all manner of germophobes. The pandemic has added to those ranks, created new ones, and, of course, proved the germophobes right. “Our customers think about those kinds of things,” he said. “They know who cleaned their RV, because they cleaned it. They know who has been allowed in the unit, because it’s their unit.”

The earliest RVs were basically tents on wheels, covered wagons that hitched to cars instead of horses. But it didn’t take long for a group of entrepreneurs to realize they could make more money by complicating things. By the late 1930s, Elkhart was already delivering extravagant travel trailers that anticipated the bigger-is-better “fifth wheels” (a technical term for a trailer that hangs over the bed of a pickup truck). Some innovations, like the slide-out sections that make an RV wider at the campsite, were widely adopted. Others were not. Long before it was acquired by Thor, Jayco made a pontoon-camper hybrid called the Camp-n-Cruise. It sold poorly. Winnebago Industries Inc., based in Iowa, briefly sold a flying RV called the Heli-Home. “It was a neat idea,” said Al Hesselbart, the retired staff historian at Elkhart’s RV/MH Hall of Fame Museum & Library, a facility dedicated to the glories of recreational vehicles and manufactured housing. “But it was one of those giant steps that was way too big for the customers.”

These days RV companies are still cramming their products full of products. Higher-end motor homes include gas fireplaces and heated tile floors. The plant manager at Rev Group Inc.’s Renegade RV factory bragged about the Amish-built cabinetry his employees were installing. An executive at Gulf Stream Coach Inc. boasted of his company’s “cradle of strength” system for lowering the vehicle’s center of gravity and making it easier to drive. At Nexus RV, co-founder Claude Donati showed off 4×4 drivetrains aimed at improving towing capacity, perfect for hauling a $200,000 sports car behind a $200,000 RV.

A Renegade RV is assembled in Bristol.

Photographer: Lyndon French for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photographer: Lyndon French for Bloomberg Businessweek

Their enthusiasm was only slightly diminished by rising production costs. Skilled workers in need of employment are hard to find in northern Indiana right now, and good ones are commanding higher wages, said Donati. Finding parts is an even bigger problem. When Nexus’ normal supplier of wheel well liners ran out of inventory this spring, the company found them on Amazon. It bought mattresses online at Wayfair and generators off the shelf at a Menards hardware store. “It’s like, do we ship it without a generator?” Donati asked. “You might be putting someone in a position not to have as much fun.”

I’d rented our Sunseeker from an outfit called Road Bear RV, which, as it turned out, was facing a similar predicament. A week before we arrived—we drove a normal rental car to get there—I got an email from the reservation desk alerting me to a pitfall of renting an RV in March: I could hook up the RV to a water supply, but I’d have to take responsibility if the pipes burst. This didn’t seem like a big deal at the time, but then the cold front swept in, promising overnight temperatures in the 20s. The safe plan, a Road Bear representative said, would be to camp without running water.

If Road Bear was worried I’d get an incomplete experience, they didn’t show it. RV rental companies, much like the rest of the industry, have spent the past year riding the Covid-19 roller coaster. Road Bear and its sister company, El Monte RV, had traditionally done most of their business with tourists from Europe, who were shut out of the U.S. by travel bans. But domestic demand was more than picking up the slack. Road Bear’s parent, a company in Auckland that had started out running helicopter tours in New Zealand, increased U.S. rental revenue 30% in the second half of 2020, compared with the year before.

The Road Bear rental office was situated in the back corner of an empty lot on Forest River’s Elkhart campus, in a corrugated metal building that would have looked to the uninitiated like a good place to do something illegal. Inside, a counter was mounted in front of the broadside of a motor home called a Coachmen Leprechaun. Would our RV lead us to a pot of gold or a pot of something else? A clerk took my credit card and handed over a packet of toilet chemicals.

We had rented the RV through Road Bear’s factory direct program, an offering it developed to help solve a key logistical problem. The company manufactures its RVs in Indiana, but its offices are near major cities. So Road Bear offers renters their choice of the company’s RVs for $9 a day to pick up a motor home in Elkhart and drive it to a rental location. After insurance, campsite fees, and gas, our trip worked out to about $170 a day.

At first glance, the Sunseeker compared well to the types of hotel rooms we could get for the money. For one thing, there was a semblance of privacy: My 7-year-old daughter claimed the loft over the cab, and my 5-year-old son slept on the pull-out sofa in the living area. My wife and I had the master bedroom at the back, with wardrobes and a television.

On the other hand, the Sunseeker was a lot more complicated to operate than a two-queen room at the Hilton. When we took possession of the motor home, a Road Bear employee spent 15 minutes walking us around the vehicle while delivering a series of commandments. Start the engine and engage the emergency brake before you extend the slide-outs. Turn off the propane before you fill the gas tank. If you must use the toilet, flush with windshield wiper fluid, because it has a lower freezing point than water.

Scenes from the road.

Photographer: Patrick Clark for Bloomberg Businessweek

We camped in Elkhart that evening, celebrating Eleanor’s birthday with McDonald’s and cheesecake, and soon realized that the Road Bear tutorial had been somewhat inadequate. The RV beeped and buzzed for reasons we couldn’t account for. The internet told us to make sure we flipped the breaker before plugging an RV into a power source, but there was no breaker in the electrical box at our first parking slot. I took a breath, imagined offing my family in an electrical explosion, and plugged in. Nothing bad happened, but a couple of hours later we had to spend 10 minutes looking for an elusive light switch. I woke up cold in the middle of the night, dialed up the thermostat, and then smelled something burning. A bit of Googling indicated that the smell was probably just construction debris left in the furnace. To be safe, I turned off the heat and went back to sleep.

I’d been warned that a new RV takes a little while to get used to, and moreover that RVing was a lifestyle for people with a certain capacity for self-reliance. RVers had to be comfortable driving a big rig and making minor repairs. Yes, they appreciated modern conveniences such as dishwashers and satellite television, but they also didn’t mind cramming themselves into tiny showers or acquiring a basic understanding of electrical system design.

Even before we left Elkhart, it was clear my family might not quite meet this description. I had bought the hatchet as a joke—it was on one of the checklists we’d found on the internet covering what to pack on an RV trip—and I figured I’d buy wood and fire-starters like any basic urbanite. But there’s something about having driven a rickety house-car up a windy Appalachian hillside that makes you feel vastly more capable than you actually are. And so I found myself making kindling at Little Beaver State Park near Beckley, W.Va. A light snow was falling, and my children pulled up their camp chairs to watch me nurse the fire while Eleanor cooked burgers on the electric stove that folded down from the motor home’s outdoor kitchen. Then my hatchet blade slipped. I didn’t feel pain, at least not at first.

Clockwise from top left: The author, grooming at Jellystone Park; dinner in Kentucky; the case for not making your own kindling; the outdoor kitchen.

Photographer: Patrick Clark for Bloomberg Businessweek

Getting to the emergency room in rural West Virginia seemed like it would be an order of magnitude harder than plugging in a motor home. My first instinct was to wrap my wound in a towel and hope. Eleanor didn’t think that was a solution and called 911. By 2 a.m.—after a 30-minute ambulance ride to Raleigh General Hospital, where the staff sewed me up and called me a cab back to the campsite—I faced a new set of questions.

Could I drive the Sunseeker with nine stitches in my hand? (I thought so.) Did Eleanor want to drive? (No. She didn’t.) Were our collective nerves too fried to face another drive through the mountains? (Yes.) Did we have enough propane in the tank to last another day of freezing temperatures? (Maybe?) In the end, we spent a rest day in Little Beaver, ordered Domino’s, and shut the doors against the cold.

The guy dressed like Ranger Smith at the camp store in Luray, Va., heard me say my name and made a crack about Clark Griswold, the everyman played by Chevy Chase who dragged his family through hilarious misadventures in the Vacation movies. I didn’t mind. Jellystone Park resort, the Yogi Bear-themed chain of RV campgrounds, felt like a party, and, after the ER visit, a relatively safe one. Kids jumped on bouncy pillows and waved at a bear who was riding around on the back of a golf cart. Adults played classic rock at respectful volumes and tended their fires.

A strange thing about RVing is that you can theoretically go anywhere, but many people take their vehicles to glorified parking lots so they can make camp 20 feet away from the next group. This is not universally true: Some stay for free at Walmart parking lots and national forests. But RVers—like motorcyclists and Jeep people—like being around their own kind. That often means in diagonal rows of RV-size spaces, each one with an electrical box, a water spigot, and a hole in the ground to connect the tube that empties waste. Usually there’s a picnic table. Sometimes there’s a way to hook up to cable TV.

Snapshots from the Clarks’ vacation, including, top left, a post-injury indulgence.

Photographer: Patrick Clark for Bloomberg Businessweek

The Luray Jellystone was a little bit like that, but its RV sites were built into a hillside and along a grassy quad, making it feel less like a parking lot and more like a summer camp, where we could enjoy the kinship of a hundred or so families who also recognized the pleasures and pains of vacationing in a house-car. The temperature had started climbing, and so we were able to plug the Sunseeker into the municipal water supply. I flipped the switch on the electric water heater (having learned to conserve propane) and took a hot shower. More important, I was finally able to complete an important rite of passage: I got to empty the wastewater tank.

Our campsite at Jellystone didn’t have a sewage hookup, and it took two laps around the park before I managed to pull up on the correct side of the communal dumping station. I affixed one end of an accordion tube to the Sunseeker’s undercarriage, screwed the other end to a concrete basin, and pulled a gray handle to empty water from the sinks and shower.

It was easier than I expected, but there was a catch. Everything on the Sunseeker was new, but the tube that Road Bear had supplied me with was not, and when I pulled the plunger, water poured through slits in its midsection. I should have realized what would happen next, but then I pulled the handle to release the toilet tank. Wastewater came pouring through the slits and onto the gravel road next to the basin. In a flash, I understood the appeal of Thor’s poop suitcase.

On the drive north from Virginia, we assessed the vacation. I had liked driving the RV, clatter and all, and loved pressing the button that made it expand, though the size of the vehicle made it inconvenient for side trips and excursions. Eleanor agreed that the Sunseeker was big enough to provide a bit of privacy, but small enough to be an intimate space for a family of four. That was nice. It had probably been a worthwhile adventure, and she would never do it again.

Which was fine. I got my first vaccine shot shortly after we returned the Sunseeker to the Road Bear office in industrial New Jersey. A few days later we booked airplane tickets to visit family in Florida. The kids went back to school full time, a triumphant moment that signaled the end of what for me had been the most difficult and best parts of the pandemic. Trying to maintain Zoom-school discipline and tending to the emotions of kids who’d been separated from their friends was terrible. On the other hand, I’ll probably never spend as much time with them again.

I didn’t know it, but when I stepped out of the puddle of wastewater at Jellystone Park, the worst of the pandemic was probably behind us in the U.S. (Fingers crossed.) There had been a water hose nearby, but I couldn’t figure out how to get it to work, so I gave up on cleaning up after myself and approached the driver behind me to apologize. It’s our first time doing this, I told him. We rented this thing. I kind of made a mess.

“That’s OK,” he said. “I hope you had a good time.”

Read next: JetBlue’s Founder Is Preparing to Launch a New Airline in a Global Pandemic