This week’s top stories:

For decades China has had one of the highest

female labor force participation rates in the world, much higher than the U.S. To help the national economy, Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong encouraged women to join the workforce; much later, the country’s one-child policy encouraged them to stay there.

But now that China needs more children it has switched tones, emphasizing women’s role as caretakers—both of the three children it now hopes they will have, but also of their elderly parents. That may not be enough to curb China’s demographic problems. In fact, it seems to be creating new ones.

In particular, women are worried that gender and pregnancy discrimination — illegal but often overlooked — will get worse. A Human Rights Watch study found that one-fifth of 2018 civil service job postings in China specified a preference for male applicants.

Employers are required to offer paid maternity leave (98 days currently) but enforcement is rare. Some companies avoid the issue entirely by requiring women to “promise” in their employment contract that they won’t marry or get pregnant.

On top of that, China has scaled back its state-sponsored childcare options, effectively pushing the childcare burden back onto working women. In 2018, women in China were spending three times as many hours as men caring for children.

Spurred by the new three-child policy, some women took to the social media platform Weibo to say they’d protest by refusing to marry and have kids at all. In response, the government deleted their Weibo accounts.

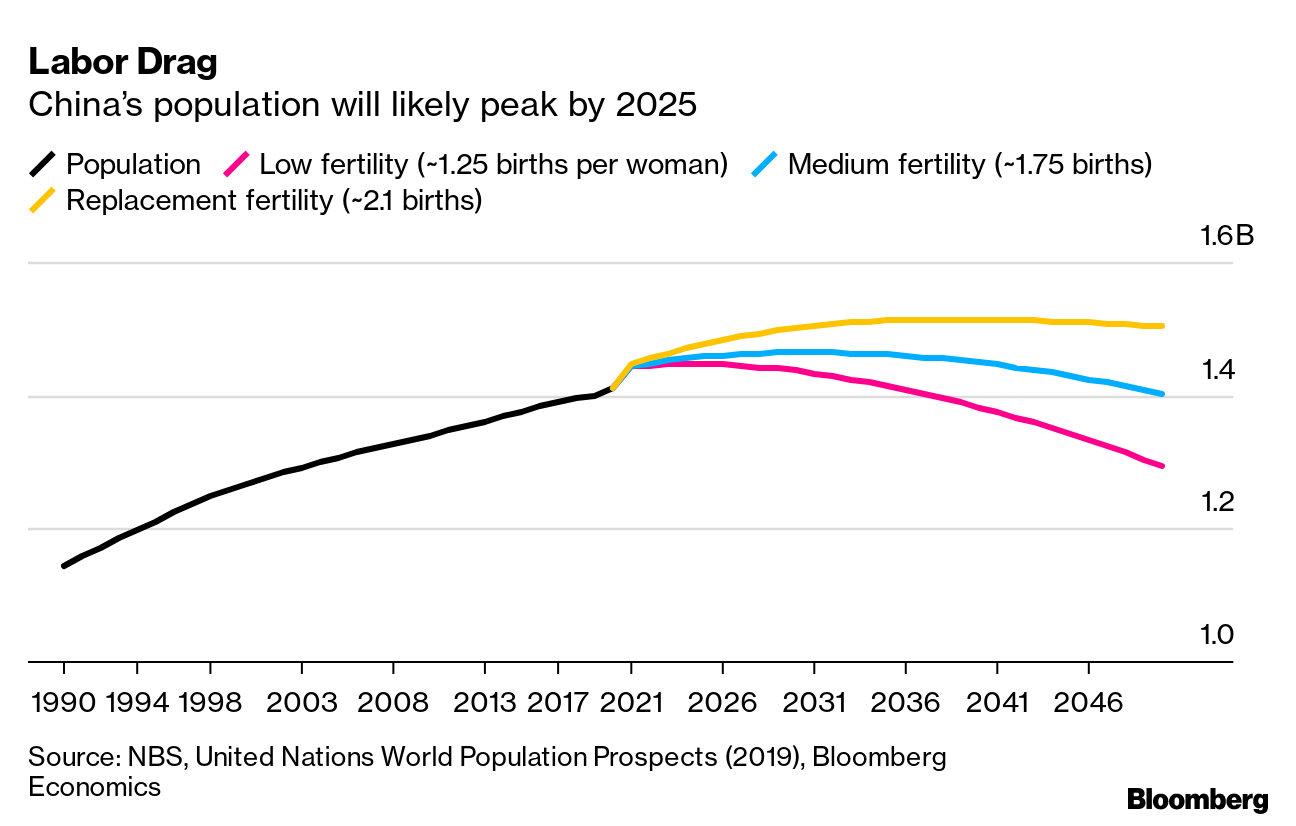

Labor Drag

China’s population will likely peak by 2025

Source: NBS, United Nations World Population Prospects (2019), Bloomberg Economics

Other east Asian countries are facing similar population declines, largely because working women are either postponing motherhood or deciding not to have kids at all. In the 1970s

South Korea urged women to have no more than two children; today, the birth rate is barely 1 birth per woman, and the average age of a first time mother is over 31. In Japan, a woman who wasn’t married by age 25 was derogatorily called a “Christmas cake,” as in, a pastry that spoils after December 25. Today, 25% of Japanese women between ages 35 and 39 have never been married, compared with just 10% a decade earlier.

They’re all backed into a version of the same demographic corner. They need women to work and to have children. But instead of implementing policies that support women’s efforts to do both, they’ve ping-ponged from one extreme to the other.

What if there were another working- and child-rearing demographic that could pick up the slack? Increasingly, men may have little choice. In China, men outnumber women by 34 million, equivalent to the entire population of California. While they may not be able to birth children, few have siblings, and in the coming decades it will be those male singletons who have to to shoulder the caregiving responsibilities for their aging parents.— Claire Suddath

By the Numbers

At the height of the pandemic, many U.S. business owners worried their customers would never come back. They should’ve spared some concern for their workers, who are quitting at increasing rates. Restaurant and hotel workers are

especially fed up — 5.6% of workers threw in the towel in May, up from 5.4% in April.

New Voices

Bloomberg News supports amplifying the voices of women and other under-represented executives across our media platforms.

“A gold medal is a gold medal, and a World Cup is a World Cup, no matter your gender.”

Maria Cantwell

U.S. Senator from Washington State, on her bill to make

pay equity a condition of federal funding for U.S. Soccer